[ad_1]

Muscle cars, SUVs, European models, and other tuner cars—peruse more Project Car Diary entries here.

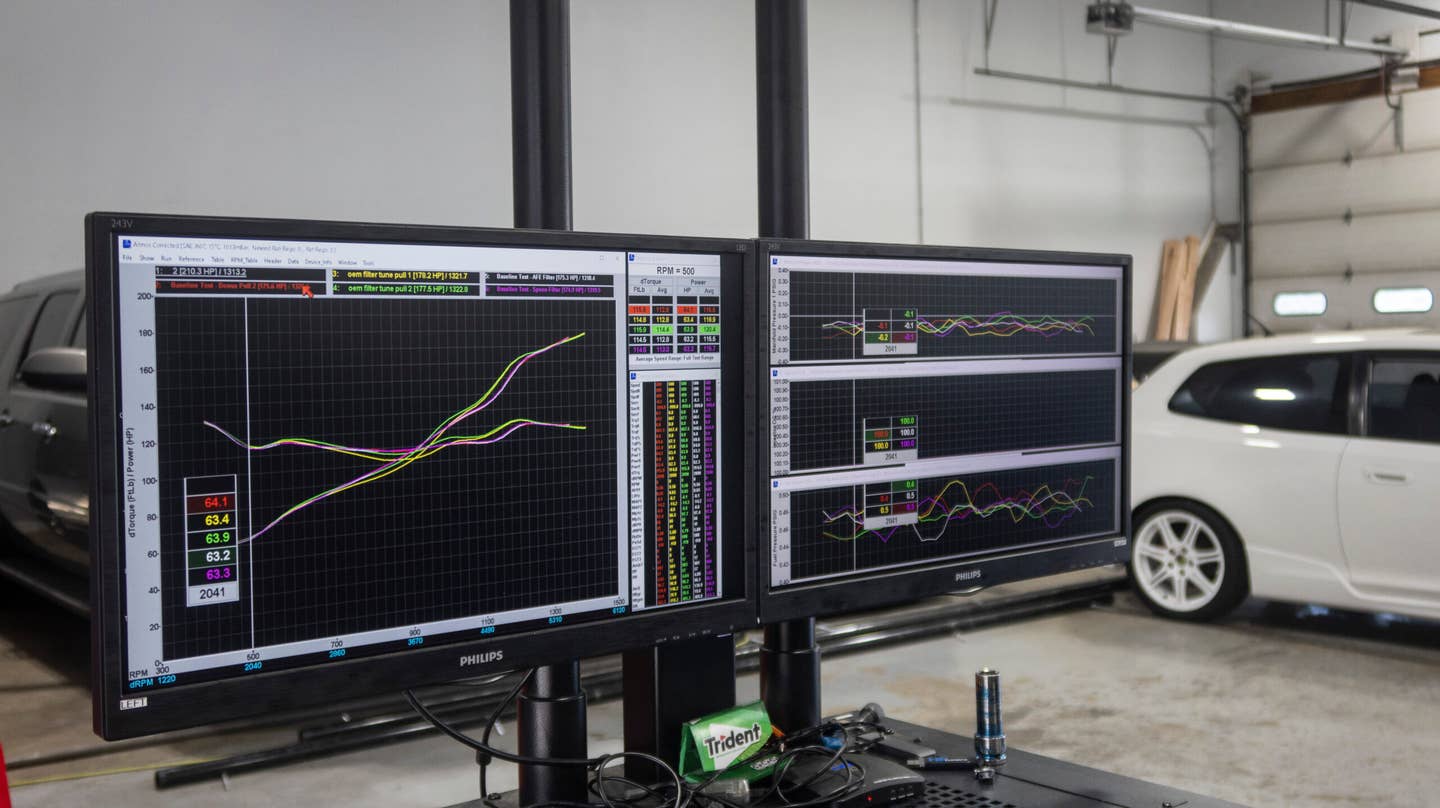

The Outcome

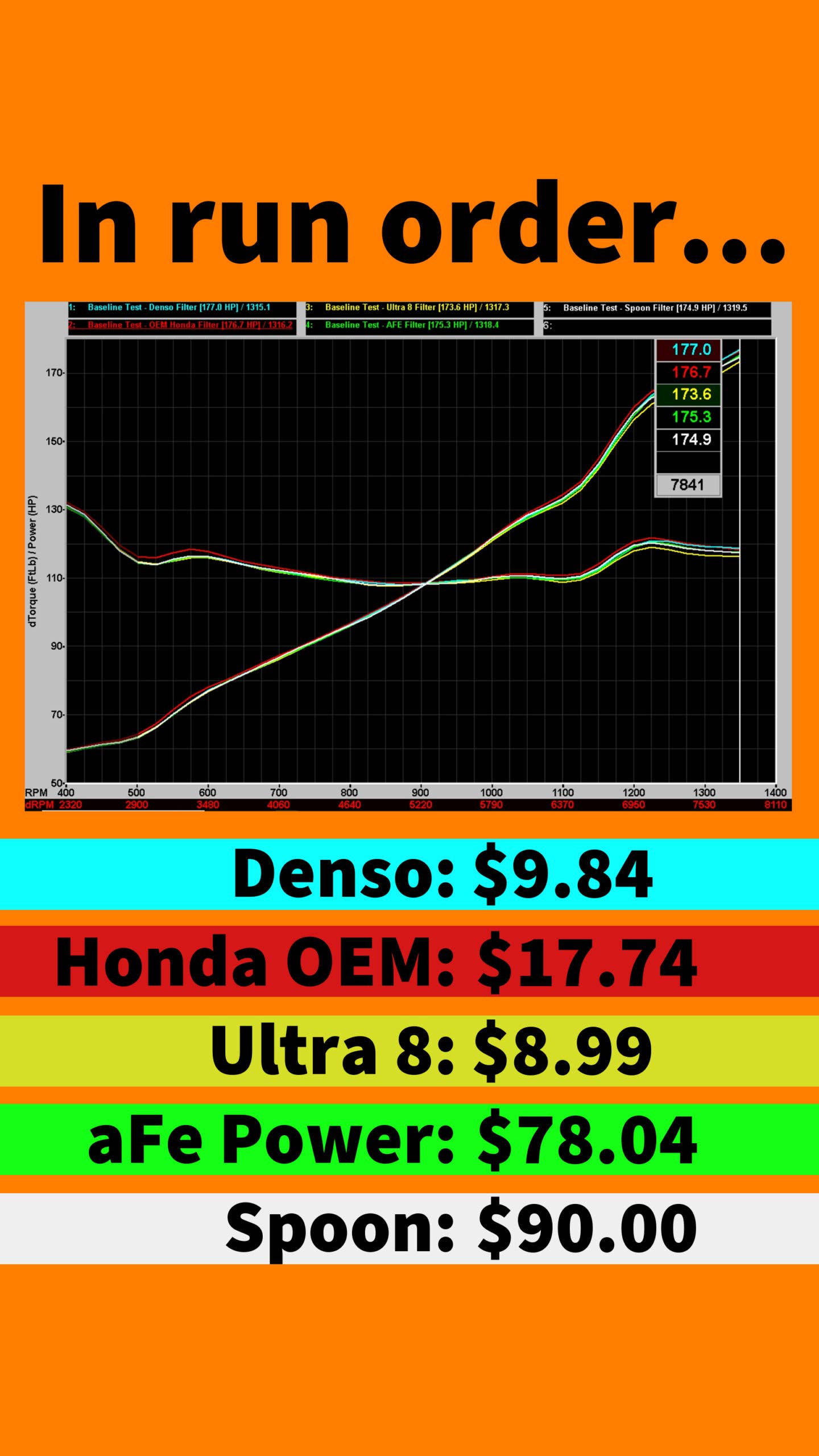

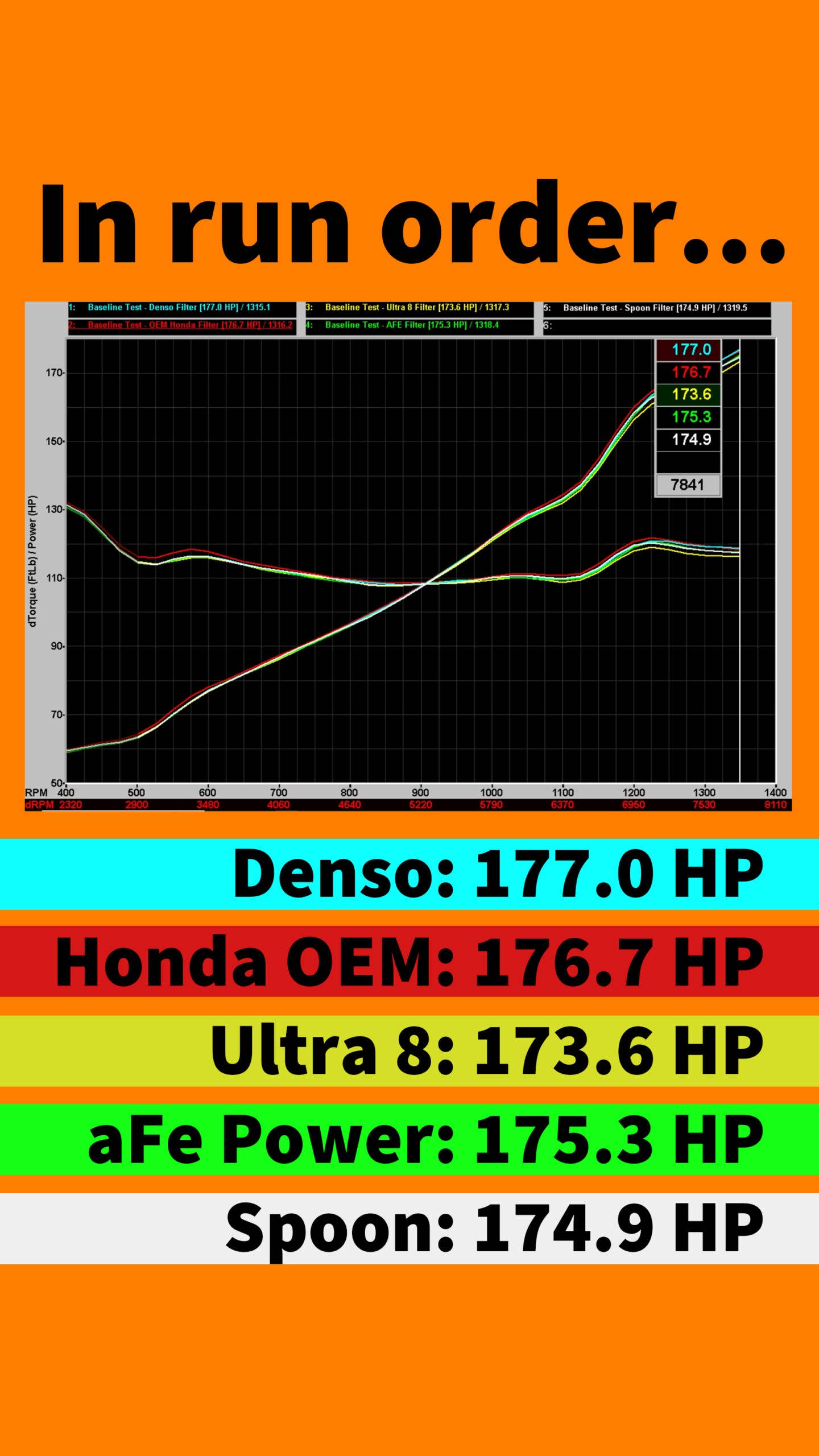

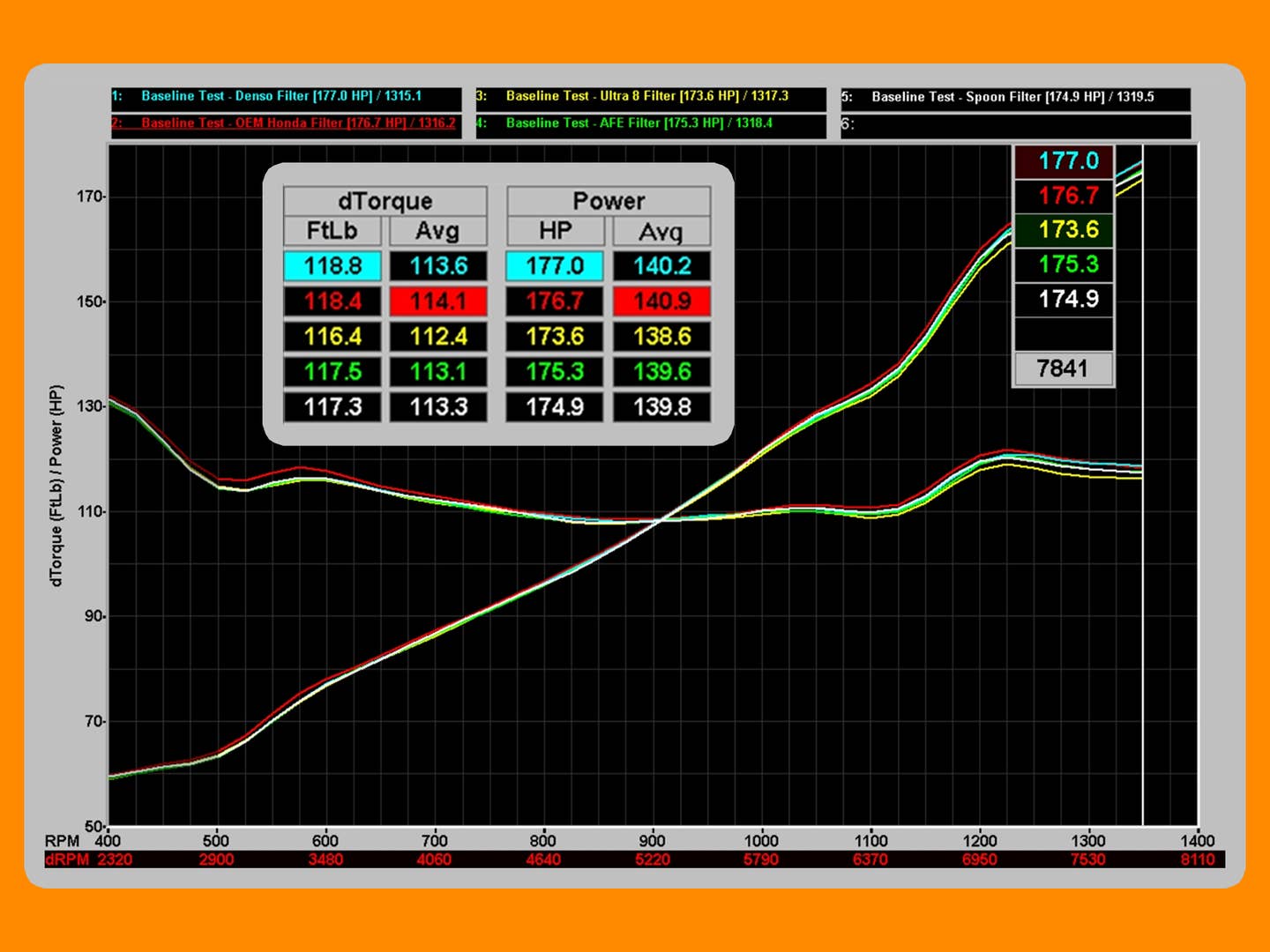

- Denso (pre-owned)—177.0 hp, 118.4 ft-lb of torque ($9.84 at RockAuto)

- Honda OEM—176.7 hp, 118.4 ft-lb of torque ($17.74 at Majestic Honda)

- Ultra 8—173.6 hp, 116.4 ft-lb of torque ($8.99 at NAPA)

- aFe Power Pro Dry S—175.3 hp, 117.5 ft-lb of torque ($78.40 at aFe Power)

- Spoon Sports—174.9 hp, 117.3 ft-lb of torque ($90.00 at Spoon USA)

The Filtration Devices

Here are the filters that were assessed and the rationale behind each choice:

- The Denso unit that was previously installed in the vehicle — I initially assumed Denso was the original equipment manufacturer for this component. However, it turned out not to be the case, but I opted to test the one already present in the car

- Honda OEM — it’s imperative to evaluate the stock filter to establish a benchmark.

- air filter housing

- Ultra 8—this was the most inexpensive air filtration option available. The local NAPA Auto Parts store offered this significantly more affordable choice compared to other auto parts retailers in the vicinity, and the cost even undercut Amazon and RockAuto after factoring in shipping costs.

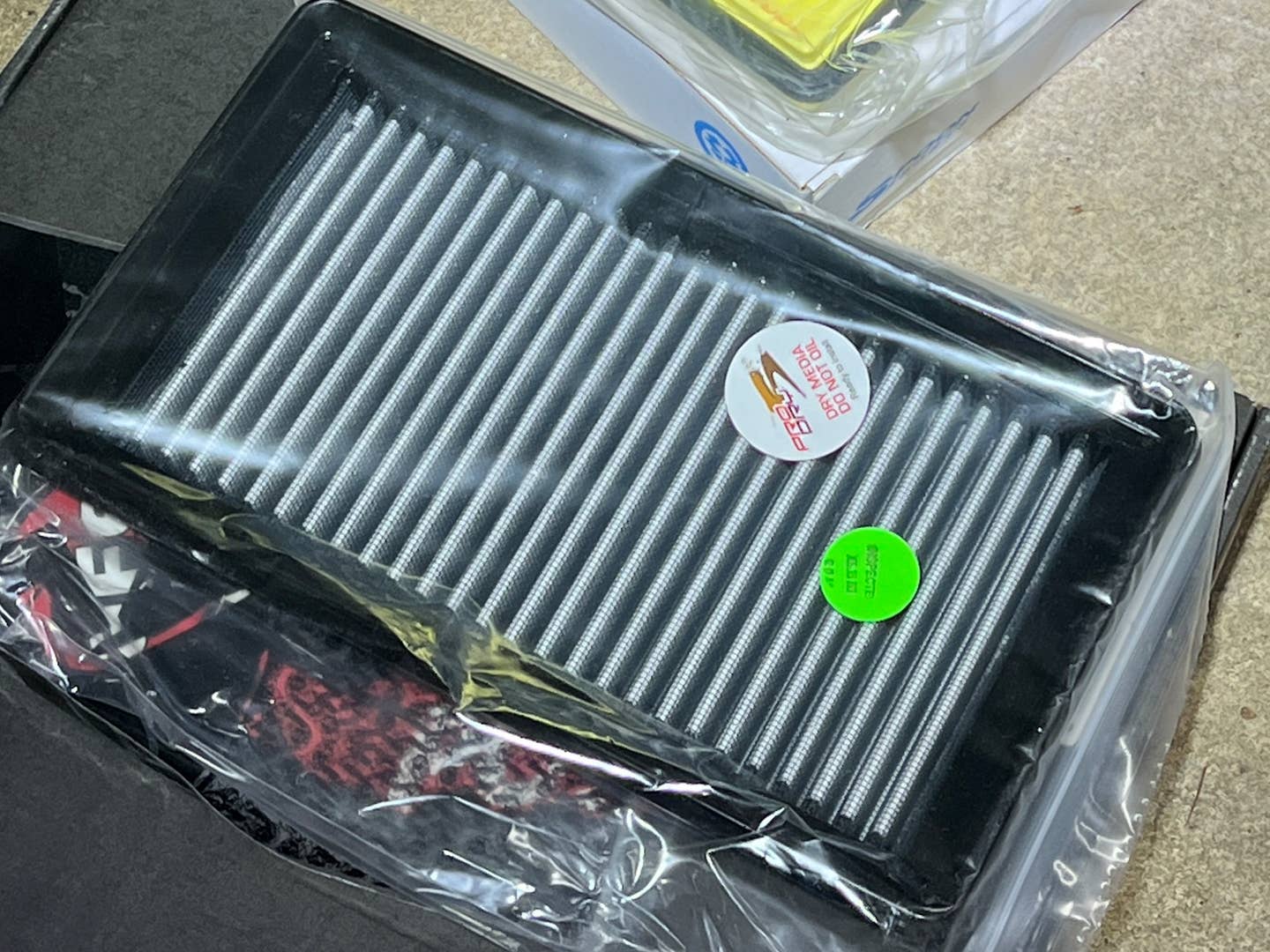

- aFe Power—a long-standing American performance tuner specializing in intake systems. They offer a high-performance oiled air filter and a dry variant (we tested the latter).

- Spoon Sports—a renowned Japanese Honda tuning specialist. While technically designed for the eighth-gen Civic Type R, this component fits the Si air filter housing (and also fits in a Honda Element, for those interested).

My approach to this examination was rather inadvertent. Upon acquiring my Civic, it came equipped with an Injen cold-air intake that negatively affected the car’s performance. After investing in professional tuning with a Hondata FlashPro, which significantly improved the vehicle’s performance—an essential step in car modifications. However, concerns arose due to the cold-air intake’s filter placement near the wheel, making it susceptible to contamination from external elements. Consequently, I embarked on sourcing components to fabricate a stock intake system, which turned out to be a surprisingly prolonged endeavor, and subsequently installed it.

To further enhance performance, I insulated the stock intake with heat-reflective gold tape and delved into air filter research. While familiar with oiled K&N filters and their purported horsepower increments, I harbored reservations towards oiled filters for reasons I’ll elaborate on later. However, I discovered that performance tuners aFe Power and Spoon Sports offer dry drop-in air filters tailored for my eighth-generation Civic, promising performance improvements. The notion of whether they truly deliver enhancements lingered, especially when contemplating investing $90 in the Spoon variant merely for the appeal of having a Spoon “component” in my vehicle for cosmetic reasons (yes, I acknowledge my peculiarity).

Eventually, an epiphany struck: Understanding the precise horsepower output of my K20Z3 engine as a benchmark for future modifications and the tuner optimizing the current setup would be exciting. Furthermore, given the ease of replacing a factory air filter in seconds, conducting multiple tests on a selection of filters wouldn’t demand significant dyno time.

In addition to the Spoon and aFe alternatives, I found it pragmatic to juxtapose them against a factory OEM filter. Furthermore, for comprehensive context, I pondered why not include the most budget-friendly filter available? Looking back, I regret not incorporating a Wix and NAPA Gold unit, as they are my usual go-tos. Nonetheless, decisions had to be made.

The Stock Filter Triumphs

Evidently, Honda’s filter is impeccably tailored for Honda’s intake mechanism, whereby in this instance, the anticipated results were duly realized.

The manufacturer of Honda’s stock filter for this vehicle is Filtech, a Europe-based supplier renowned for furnishing various types of industrial air filters as original equipment to numerous companies.

If you possess a stock or minimally modified Honda, I emphatically advocate utilizing this filter, as it evidently garners optimal performance and exhibits commendable filtration capabilities—a testament to the enduring reliability of eighth-gen Civics, with no reported concerns regarding particle intake-related reliability issues.

Vehicle and Test Conditions

My eighth-gen Civic has slightly surpassed the 100,000-mile mark, underwent valve lash adjustment by a mechanic a few thousand miles back, and currently operates with fresh Eneos oil and relatively new OEM-spec NGK laser iridium spark plugs. Moreover, it has fresh OEM coolant installed. The sole performance modification entails an A’pexi World Sport 2 exhaust—selected based on sound preferences rather than speed enhancements.

We conducted our experiment on a balmy November day at Evans Tuning in Pennsylvania (approximately 60 degrees Fahrenheit ambient, dry air) utilizing ProHub Dynamometers. Jeff Evans, the tuner who has collaborated with my vehicle on several occasions, noted that this dyno setup typically registers at the lower end and allows for a margin of error of approximately half a horsepower.

Key Points for You

Reasons for Avoiding Oiled Filters

Oiled air filters, such as those offered by K&N, typically advertise superior airflow compared to stock filters with robust filtration capabilities. The fundamental concept behind oiled filters implies that they can provide less restrictive media than dry filters by relyingon a slender coat of oil to seize the approaching debris complementing the paper and plastic. The conceptual allure is that air can circulate through and around oil more efficiently than solid filter material.

Andrew P. Collins

Doubters of oiled filters frequently mention worries that the oil will harm intake sensors, whereas advocates and representatives from the vendors maintain that they have conducted extensive testing and are fervent that this is a non-issue (in fact, I recently heard a K&N representative express this at SEMA last week).

I assume what occurs is that individuals purchase these items, and then when it comes to reapplying oil to them, they go overboard or insufficient, which leads to problems with intake sensor damage or insufficient filtration. The reason I personally prefer not to handle them is somewhat related but more trivial – I simply loathe oiling air filters. Additionally, I anticipate that I would most likely either over-oil or under-oil it myself.

In a previous era, I worked as a guide in Australia, guiding groups of individuals on lengthy off-road excursions with motorcycles and trucks in the outback. We utilized oiled filters on our rental bikes, and one of my responsibilities was maintaining those filters clean. And goodness did I grow to abhor that task. Numerous motorcycles pushing hard through severe conditions for eight hours daily? Indeed, we consumed air filters like Derek Zoolander used cotton balls in that scene following his coal mining montage. The turpentine we utilized for cleaning them was pungent, and the filter oil was disgustingly adhesive–I manipulated it into the filters with my hands so I had to fully immerse myself into it, as well. Never again.

But Wait—We Still Left the Dyno With New Horsepower

Andrew P. Collins

This brief filter comparison test was merely the secondary goal for my trip to Evans Tuning. The primary goal was to perform a general health assessment for my Civic. Granted, it felt and sounded like it was operating smoothly, and I was aware of the Honda factory power specifications, but what output was this car specifically delivering? The only method to ascertain the real answer is to dyno it.

Another principal objective was to have the car fine-tuned to operate as optimally as possible. Indeed, you can fine-tune a stock car. Naturally, having no modifications beyond a modest cat-back exhaust implies the tuner won’t be capable of achieving a massive power boost. Nevertheless, they can refine the performance of the distinct engine in subtle but meaningful ways–which will be the topic for discussion in an upcoming Project Car Diary entry.

[ad_2]