[ad_1]

Imagine the worldwide scenario in the early 1970s when William Towns, the visionary behind the Aston Martin Lagonda Series 2, was translating ideas onto paper. Soaring oil prices and a parallel crisis in the steel sector had severely impacted the economies of Aston Martin’s primary market, the U.S., and its home nation, the U.K.

In the midst of high unemployment and inflation, the challenging times carried on through the middle of the decade. By early 1976, with Towns’ sketches evolving into clay models, there was a glimmer of hope on the economic horizon, albeit faint. Aston Martin’s future hung in the balance. Having changed hands twice in a span of four years, the company’s new leadership, although enthusiastic, was in dire need of a breakthrough.

Towns had initially been recruited to design car seats during Aston Martin’s prosperous era in the mid-1960s; merely two years later, he had progressed to shaping the iconic DBS coupe. Now, faced with a pivotal moment, the Lagonda Series 2 needed to do more than just make a statement – it had to create seismic ripples across the industry. If the term “disrupt” held the same weight in corporate circles as it does today, it would have been uttered in a motivational speech to galvanize the team.

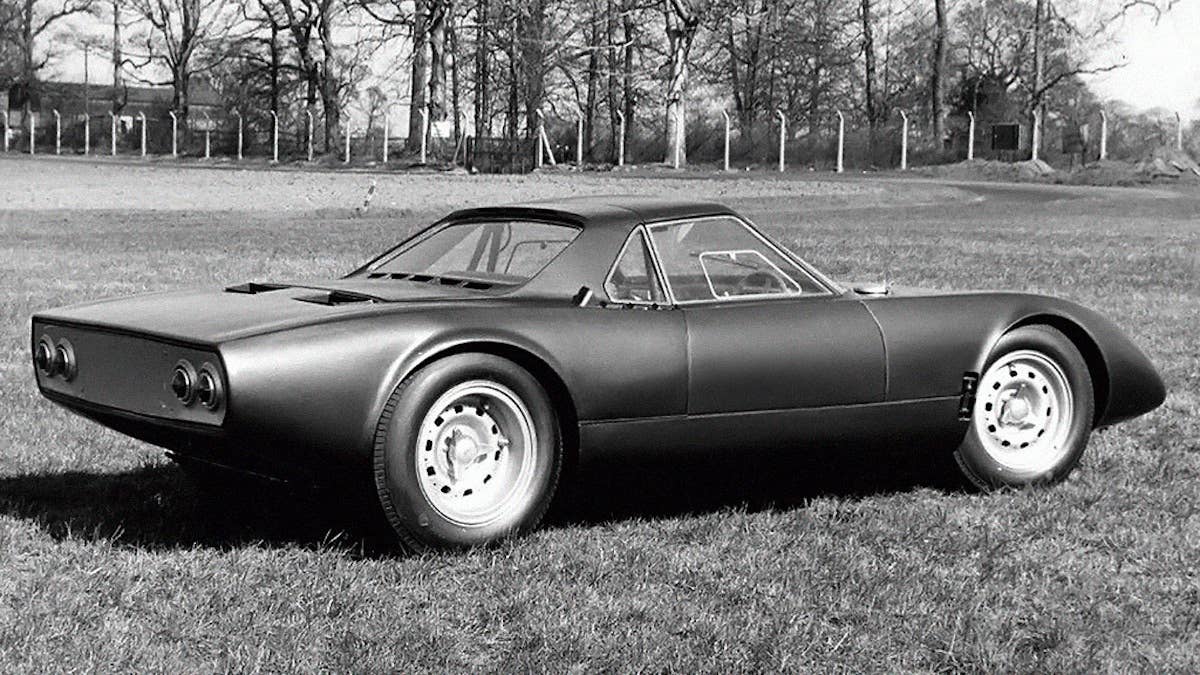

In his notebooks, Towns had been experimenting with the concept of a sedan inspired by the angular design of contemporary sports cars, particularly those crafted by Bertone’s Marcello Gandini (like the Lamborghini Countach) and Giorgietto Giugiaro (such as the Lotus Esprit), alongside his own invention, the Rover-BRM prototype from a prior employer.

When discussions on revitalizing Lagonda, the historic nameplate acquired by Aston Martin after World War II, commenced among his new superiors, Towns was clear on what needed to be done. As the ’70s progressed, his foray into avant-garde design would set the course for Aston’s future.

Build or Bust

February 1976 marked a turning point akin to a high-stakes “garage deadline” reality show. A Lagonda prototype had to be completed in time for the British Motor Show at Earls Court in London. With only eight months until the show, company executives aimed to secure adequate orders to sustain Aston Martin through the subsequent development phase. The fate of an illustrious car brand hung precariously in the balance.

While the team, under the leadership of chief engineer Mike Loasby, raced to construct a showcase car, pressure mounted from above. Aston’s fresh owners were eager to emerge from the London event with substantial orders and reinvigorated strength in the luxury car market. Lagonda represented the golden ticket, a last-ditch effort to dodge insolvency. After a series of close shaves, this became Aston’s make-or-break juncture.

Starting From a Clean Slate

In 1972, industrialist David Brown, the “DB” in DB5, had cleared the company’s debts and offloaded Aston Martin to a Birmingham-based investment group for the cost of a casual lunch. The economic turmoil struck in 1973, leading Aston to declare insolvency in late 1974. The closure came abruptly; employees returning after the Christmas break were met with locked doors. Renowned TV anchor Walter Cronkite, a car aficionado who had raced a Lancia at the 12 Hours of Sebring in 1959, bid farewell to Aston Martin on CBS Evening News.

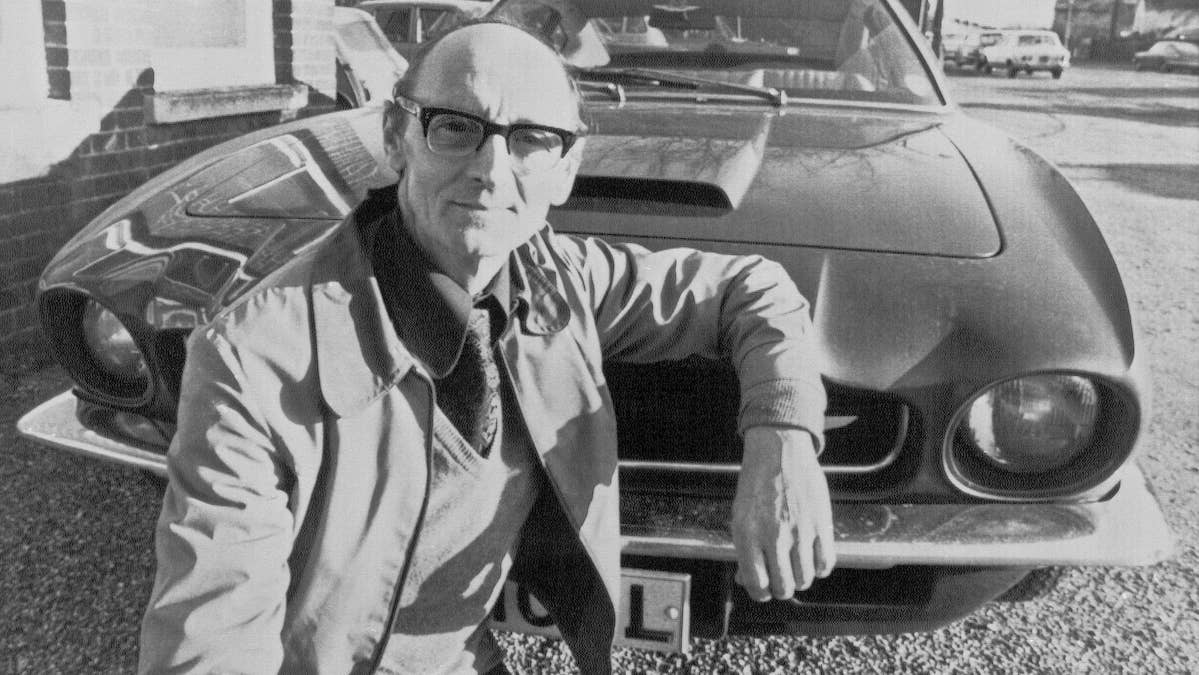

Enter Peter Sprague. A tall and reserved American who had amassed wealth in the burgeoning high-tech realm, Sprague was a pivotal figure in a British-American group that assumed control of Aston in early 1975. The British media cautiously observed him and his British co-director, Alan Curtis, an engineer and architect. Surveying the desolate Newport Pagnell workshop and pondering ways to entice back production staff lured away by Rolls Royce, the partners quietly deliberated on a strategic roadmap. Central to their plan was the reintroduction of Lagonda, diversifying Aston’s product line with a new, higher-volume segment: a luxury sedan.

Whispers surfaced about the company shifting focus away from sports cars, Aston’s traditional forte since the post-WWII era, a move some board members believed forthcoming due to potential legislative measures by policymakers emphasizing auto safety. The specter of challenges in compliance had loomed since the publication of Ralph Nader’s contentious Unsafe at Any Speed manifesto.

Exploring the Lagonda storyline was not an unexpected decision. During 1974, the business had resurrected the brand, which originated in 1906 and was last seen in the early 1960s for a sedan called the Rapide based on the DB4. The debut of the Lagonda Series 1, derived from the DBS, captivated attention at the 1974 London exhibition, yet only a few individuals were willing to spend £14,000 (equivalent to $180,000 today) on an elongated, four-door GT. Just seven Series 1 models were produced before the endeavor was abandoned.

With a modest injection of funds, a new initiative was undertaken. The Aston Martin Lagonda Series 2 would merge conventional artisanal techniques with avant-garde design and cutting-edge electronics. Priced at over £20,000 (approximately $200,000 adjusted for inflation), it would compete with elite sedans from Bentley and Rolls Royce. The interior would showcase typical elements like leather and fine British wool crafted by Wilton, a renowned carpet maker. Above all, it would signify Aston Martin’s claim to the future of luxury, intriguing affluent, futuristic-oriented buyers. Back then, just as now, many such buyers hailed from oil-rich countries in the Middle East.

A different, more pragmatic reason for Aston’s executives to focus on a sedan rather than a coupe emerged. If potential buyers of the latest AM V8 believed a new two-door variant was in the works, they might delay their purchases. In its vulnerable state, Aston couldn’t afford to risk losing that revenue stream.

By mid-1976, Loasby and his team were working tirelessly to build a prototype. As time passed, it became evident that the Series 2 would either rescue the company or push everyone involved to the edge of collapse. Ultimately, the revolutionary, perplexingly intricate, and unforgettable sedan would accomplish a bit of both.

Only The Coolest Technology

This specific Lagonda Series 2, a 1985 model belonging to South Florida dealership The Barn Miami, recently garnered The Drive‘s Coolest Tech accolade as part of the latest Virtual Radwood event. Despite rolling off the production line at Aston’s Newport Pagnell facility almost ten years after the original Lagonda debuted at London’s Earls Court, the disparities between it and the first Series 2 customer cars delivered in 1979 are minimal.

The 5.3-liter, dual-overhead-cam V8 bears resemblance to that found in the AM V8 coupe of its era. To accommodate the torque requirements of the heavier sedan, alterations were made to the inlet manifold, and different heads with larger valves were added to compensate for a reduced air box fitted into the Series 2’s more confined engine bay. In its revised state, the Weber-carbureted V8 generated 280 horsepower at 5,000 rpm and 350 lb-ft of torque at 4,500 rpm. (Although a turbocharged version producing 380 HP underwent testing, it was later abandoned due to reliability concerns.) Attached to the crankshaft was the same Chrysler TorqueFlite three-speed automatic transmission used in the Maserati Quattroporte during that period.

The conventional suspension of the ’85, like all Series 2s, consists of unequal wishbones, coil springs, and standard telescopic shocks upfront. In the rear, it features the AM V8’s typical de Dion tube, Watts linkage, and trailing links, with the addition of Koni self-leveling shocks by Loasby’s team to manage extra passengers and cargo.

Compared to traditional sedans, the futuristic design by Towns clearly indicated that the Lagonda was ahead of its time, despite its engine and suspension being merely equal to other luxury vehicles. Inside, however, the future was carefully integrated into the dashboard design.

A Great Success, and That Annoying Dashboard

Due to the dedication of Loasby and his team, a Series 2 prototype made its debut on the show floor at Earls Court in October 1976 as planned. Although not yet production-ready—it couldn’t even run under its own power; BBC footage of the prototype in motion showed it coasting downhill, unbeknownst to viewers—the Aston Martin display attracted significant attention, and the company received 76 deposit checks, mostly for Lagondas. To spectators, it represented a technological breakthrough of the electronic era.

An interior demonstration specially designed for the Series 2 allowed visitors to have an unobstructed view of the NASA-inspired dashboard cluster. Over 40 touch-sensitive buttons managed all the car’s operations: from pop-up headlights and power windows to air conditioning, cruise control, door locks, and memory-adjustable seats. The inclusion of a digital LED display, a first for a production car, provided information on speed, distance traveled, and fuel efficiency. The unique single-spoke steering wheel offered a clear view of the intricate interface.

After the show, as the initial excitement subsided and the development team shifted their focus to delivering a final product, the optimism surrounding the Series 2’s complex, microprocessor-based instrumentation turned into concern. Development setbacks and a monumental troubleshooting effort threatened the progress of the entire project. Why had the company taken such a significant leap with all that flashy technology?

For those familiar with Aston’s new ownership, the rationale behind this decision was not surprising.

Early Series 2 interior., Wikipedia

In 1975, a change in ownership handed Aston to a British-American partnership co-led by the mentioned Sprague, a businessperson who acquired National Semiconductor in 1967, marking him as Silicon Valley’s pioneer venture capitalist. Celebrated in media, Sprague and his co-leaders “rescued” Aston Martin, although the company’s future remained uncertain. They were eager to showcase the engineering prowess, with the lore suggesting that chief engineer Loasby drew inspiration for the Series 2’s revolutionary digital instrumentation and controls during a visit to National Semiconductor’s California headquarters, captivated by their futuristic touch-sensitive elevator buttons.

During the Series 2 prototype phase, Fotherby Willis electronics from West Yorkshire first developed the instruments. Financial issues soon removed them from the equation, leading Aston Martin co-chairman Alan Curtis to seek assistance from Cranfield Institute of Technology’s renowned Centre for Aeronautics. The outcomes, though advanced, fell short for a production car, as recounted by Loasby in David Dowsey’s 2007 book, Aston Martin: Power, Beauty and Soul.

“Curtis made an error by engaging Cranfield for the electronics. Never involve academics since they won’t finish the job or make it functional. Despite their technological edge, Cranfield’s handling of the electronics was a disaster due to their detachment from practical automotive constraints,” shared Mike Loasby, chief engineer.

As detailed in Sprague’s account of the project, the team employed the costly IMP-16 printed circuit card from National Semiconductor to power the Series 2’s electronics. Being the initial multi-chip 16-bit microprocessor, each unit cost around $1,400 (adjusted for 1977 inflation). “While we were working on it, Apple debuted their first computer,” reflected Sprague. “We swiftly learned that the automotive settings impose more significant challenges compared to modern aircraft, demanding flawless operation under extreme temperature ranges.”

The production phase continued into 1977, as Loasby recalled:

“In 1977, we faced a critical development juncture with the car. At times, we felt we mishandled the whole process. Underestimating the development period for a car packed with automotive innovations, along with uncertain cost estimates, created challenges. By March 1978, we managed to navigate the development hurdles after making essential adjustments,” admitted Mike Loasby, chief engineer.

One Final Embarrassing Incident

In reality, another significant obstacle loomed ahead. In April 1978, a meticulously planned press event at Woburn Abbey turned into a severe test for the development team’s resolve.

The first Series 2 was designated for Lady Tavistock, a banking heiress and spouse of Robin Russell, the Marquess of Tavistock (now the 14th Duke of Bedford). Frustrated by the delayed delivery of the car she had purchased as a gift for her husband, Lady Tavistock, who splurged £32,500 on her Diners Club card, awaited the Series 2 at Woburn Abbey amidst a media frenzy.

However, the situation turned anything but favorable. Despite the efforts of fourteen mechanics toiling tirelessly, the Cranfield-made electrical system refused to cooperate. The IMP-16 chip, as recollected by Sprague, kept causing malfunctions. Despite the setbacks, the event proceeded as planned, culminating in an embarrassing scenario where Lady Tavistock’s Series 2 had to be manually pushed to the waiting journalists.

In the Dowsey book, David Flint, Aston Martin’s manufacturing director at the time, reflected on the ordeal:

“We labored tirelessly for forty-eight hours attempting to install the harness from Cranfield Institute of Technology. As we approached completion, we were instructed to immediately send out the car. Fatigued, I refused to proceed, stating, ‘If you want this car out now, push it yourself.'”

After declaring “I shall depart.’, I proceeded to my residence.”